The Hidden Reality of Rampant Settlements in Dowry Cases - A Data Based Study

I sat down this week and analyzed the nature of 'compromises' (aka settlements) done for the 498a cases.

Summary

I sat down this week and analyzed the nature of ‘compromises’ (aka settlements) done for the 498a cases.

If you don’t know already, IPC 498a or BNS 85 is the law that punishes the husband and his family for dowry harassment against the wife.

Raw Data

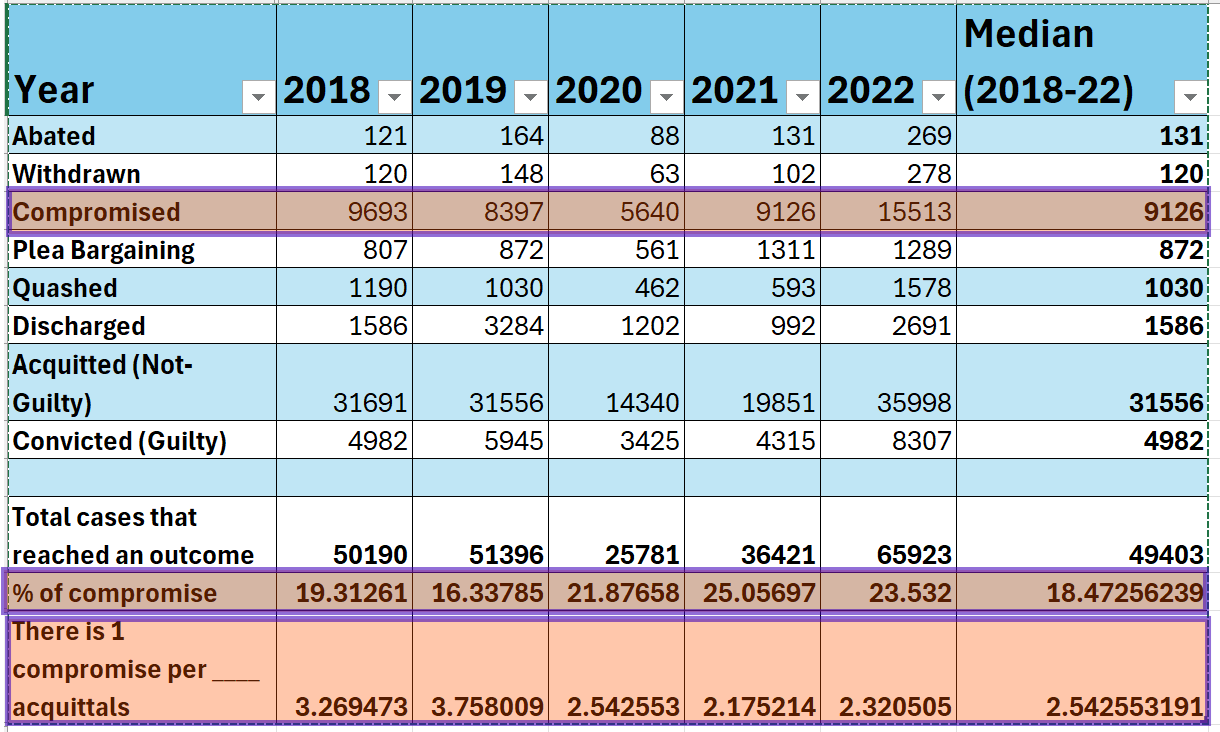

I collated the following raw data for the 5 years (2018 to 2022) from the NCRB’s Crime In India Reports.

The following table shows number of all cases that reached some kind of outcome in each year.

Caveats

Despite the numbers looking exact, there are the following loopholes or caveats that we need to understand.

- The compromise numbers counted here are ones after filing an FIR. The actual numbers might be even more, as many states do not file an FIR directly. For example, in Tamil Nadu, they file CSR and try to do mediation in police station, holding the husband in a precarious position.

- The numbers shown in each year are those that came to some kind of conclusion in that year, not the ones filed in that year.

- There is a chance of settlements being classified as acquittals and discharges too, as sometimes the courts write acquittal/discharge orders based on the settlement agreement between the wife and the husband.

Insights from the data

Apart from the open secret that the conviction rates are very low, let’s focus on compromise-related insights.

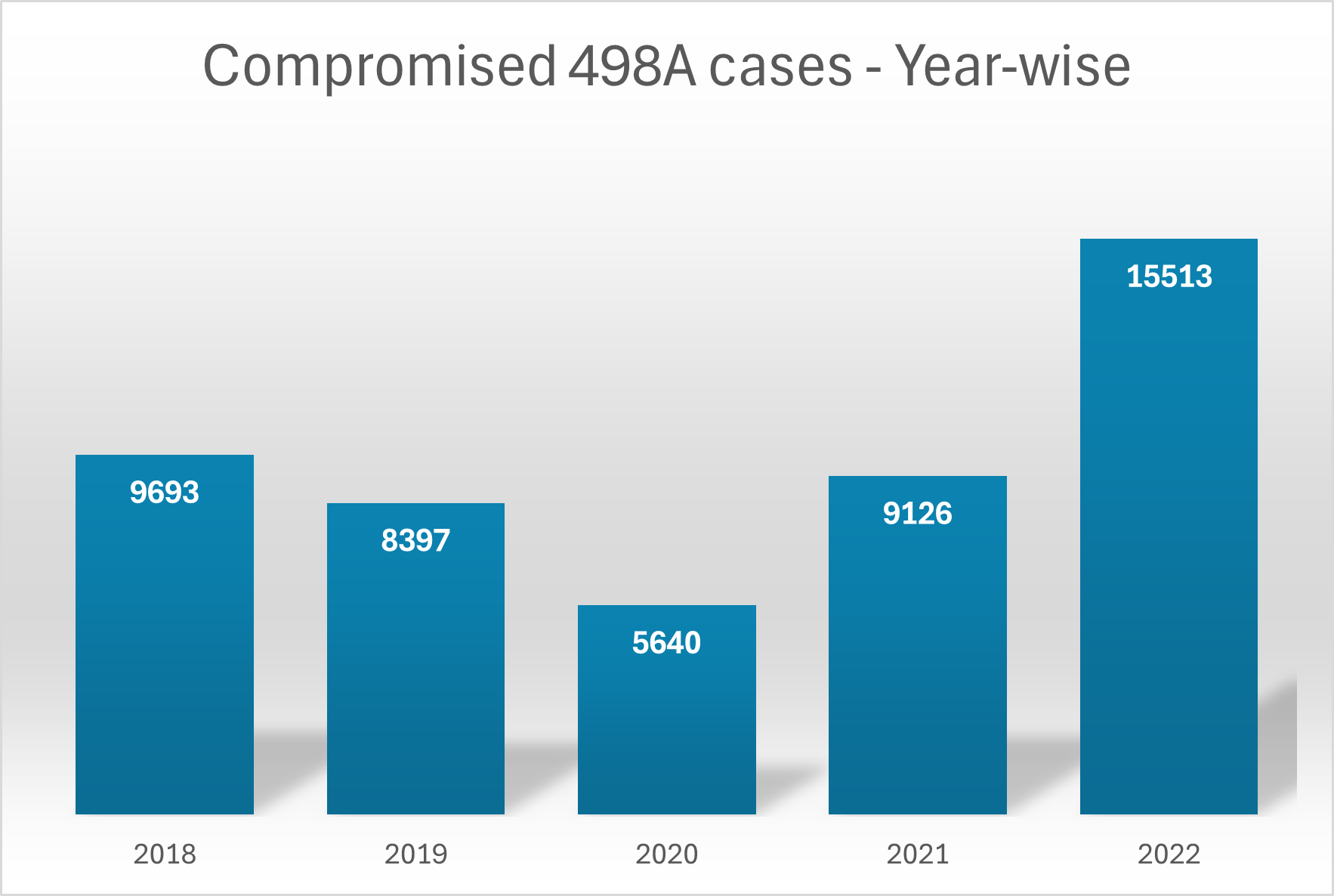

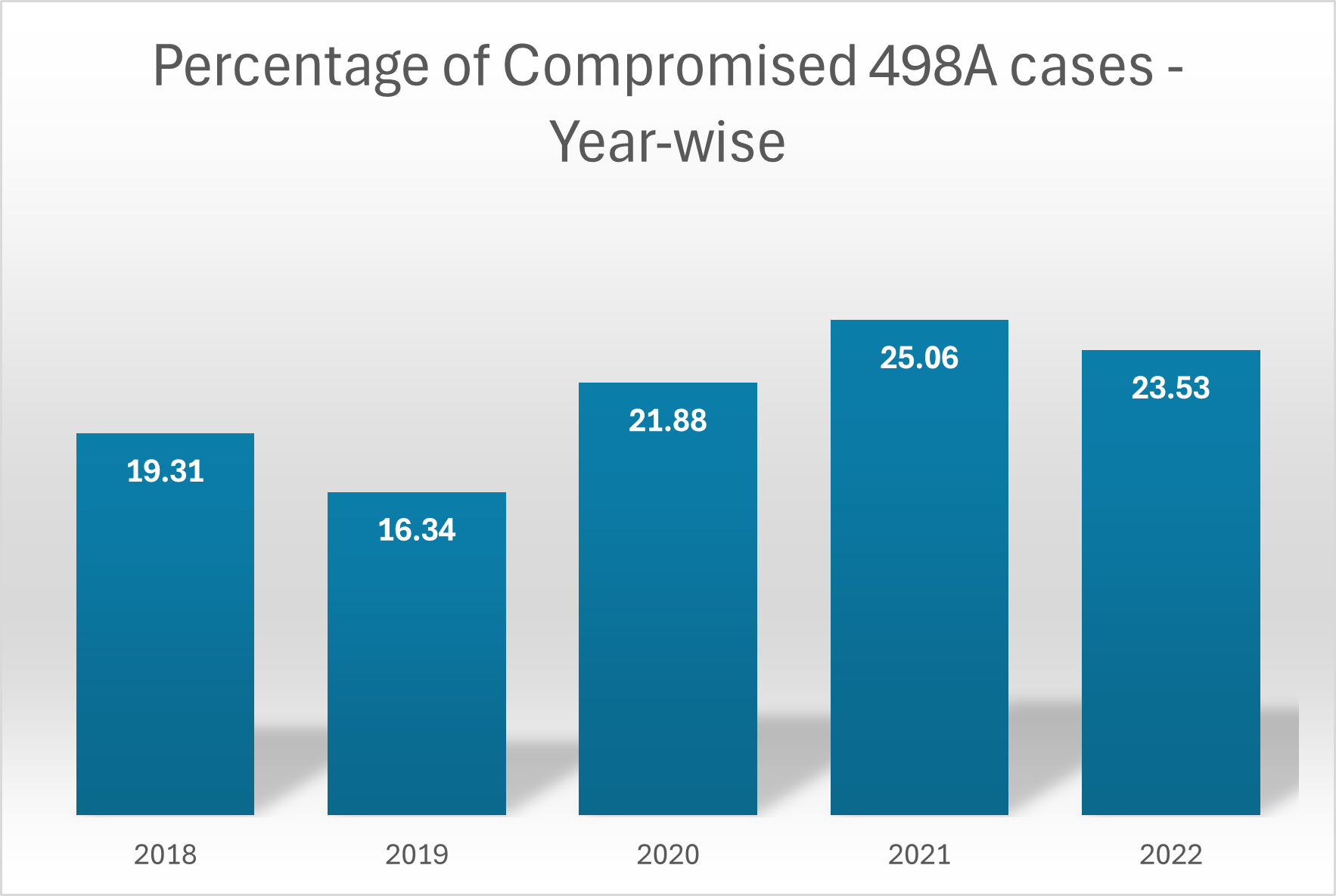

Growing Compromises: The percentage of cases settled through compromise rises from 19.31% in 2018 to 23.53% in 2022. This means nearly 1 in 5 cases ended in a settlement as of 2022.

Compromises per Acquittal: For every 2.3 acquittals (‘not guilty’ decisions), one compromise happened in 2022. This should also be added to the official acquittal rates in NCRB, but they are not! Funny right? That’s a different issue altogether, which we may write about in the future.

Costs in running a 498A Case

To understand the dynamics for settlements, we need to understand the cost implications for men and women in fighting a 498A case.

| Type of Cost | For Men | For Women |

|---|---|---|

| Legal Cost | Men have to engage a lawyer as soon as the complaint is filed, for bail proceedings. There are no free legal services offered to men (unless they prove that they are really paupers). So heavy cost. |

The state runs the case through public prosecutors, so the woman does not even need to engage a lawyer. Even if they feel like they need a lawyer for miscellaneous issues, they can get free legal aid from the lawyers from Legal Services Authority. So, no cost. |

| Travel Cost | 498a is strategically lodged in a jurisdiction away from the man’s house and near the woman’s house typically. This means that the man has to travel for each court date. So, heavy cost. |

Typically the cases are filed in jurisdiction near to the woman’s house. So, no cost. |

| Cost due to lost earnings | The accused needs to be present in all court dates. Exceptions are difficult to get. So, they need to take leaves to attend court dates. So, heavy cost. |

Woman does not need to be present in any court dates other than her evidence dates. So, in total 2-3 dates are the ones where her presence is required. So, very low cost. |

| Cost of lost Employment Opportunities | Men accused under 498A often face issues in employment background checks, as a pending case can result in a ‘red’ report, affecting their job prospects. So, heavy cost. |

Women filing the case do not have criminal cases against them, so employment background checks do not pose a problem. So, no cost. |

| Bail-Related Cost | Men often face immediate arrest under 498A unless they secure anticipatory bail, which involves additional legal fees, court applications, and stress. So, heavy cost. |

Women filing the complaint face no such requirement, as they are not the accused. The state handles prosecution without any bail-related burden on them. So, no cost. |

| Social Stigma Cost | Men accused under 498A often face societal judgment, loss of reputation, and isolation, even before guilt is proven. This can affect job prospects and relationships. So, heavy cost. |

Women filing the case are typically viewed as victims, gaining sympathy and support from society and family. So, no cost or even a social gain. |

| Family Involvement Cost | The man’s family (e.g., parents, siblings) can also be implicated in 498A cases, leading to additional legal and emotional strain for multiple members. So, heavy cost. |

The woman’s family typically supports her case without being dragged into legal proceedings as accused parties. So, no cost. |

Why settle at all?

Given the stark disparity in costs outlined above, a natural question arises: Why would women settle at all? On the surface, it seems they have little to lose and everything to gain. With no legal fees, minimal travel or time commitments, societal sympathy, and the potential for financial gain, the system appears heavily tilted in their favor.

Men, on the other hand, are burdened with heavy financial, emotional, and social costs from the moment a 498A complaint is filed. So why wouldn’t women simply let the case run its full course to maximize their advantages?

Is settlement a tool for extortion?

The answer lies in the dynamics of settlement itself, which often reveals a troubling pattern: settlement as a tool for extortion. For women, the decision to settle isn’t necessarily about avoiding losses—since they incur almost none—but about capitalizing on the immense pressure the legal process places on men.

The man, facing mounting legal bills, lost earnings, societal stigma, and the threat of arrest or prolonged litigation, is often desperate for a way out. This desperation creates an opportunity for women (or their families) to demand substantial financial settlements—sometimes far exceeding what might be awarded in court—as a condition for dropping the case.

This phenomenon turns the settlement process into a strategic move rather than a compromise. Women, supported by a system that requires little from them while exacting a heavy toll on men, can leverage the threat of continued litigation to extract money.

For instance, a man might be coerced into paying lakhs of rupees or transferring property just to avoid years of court battles and the risk of conviction, even if the case against him is weak or fabricated. The lack of accountability for false complaints under 498A further emboldens this approach, as women face no real consequences for exaggerating or misrepresenting claims.

Reconciliation or Exploitation?

In this light, settlement becomes less about justice or reconciliation and more about financial exploitation. Men, trapped by the sheer weight of the costs they bear, see paying up as the lesser evil compared to the prolonged agony of fighting the case.

Meanwhile, misguided or bad women (not the innocent ones), with no significant losses and the backing of a sympathetic legal and social framework, can treat the process as a risk-free avenue for profit.

This imbalance raises serious questions about the fairness of the system and the unintended ways it incentivizes the use of 498A as a weapon for monetary gain rather than a shield against genuine harassment.

Now, what do we do?

The increasing trend of compromises (peaking at 15513 in 2022) underscores the need for reforms to ensure Section 498A stops being misused for monetary gain. Some ways to accomplish that could be:

Stricter Evidence Standards To Start Litigation: Implement stricter guidelines for filing 498A cases, requiring concrete evidence of cruelty at the outset itself to prevent baseless claims that are later used to pressure the accused into settlements.

Penalties for False Claims: Establish clear legal consequences for those who misuse 498A, such as fines or imprisonment for proven false allegations, to deter individuals from filing cases as a tool for extortion or harassment.

Accountability for Misusers: Create a mechanism to track and investigate cases where compromises result in large financial settlements, ensuring that settlements are not coerced and holding complainants accountable if evidence suggests the case was filed with malicious intent.

Judicial Oversight on Settlements: Require court approval for all 498A settlements, with judges reviewing the terms to ensure they are fair and not exploitative, preventing the accused from being unfairly pressured into large payouts.

Video Conferencing as the Norm: Make video conferencing a standard practice for marital dispute trials, rather than an exception, to reduce the travel burden and costs for the accused, who often have to travel long distances for court dates, while ensuring timely proceedings.

Fast-Track Trials: Speed up the judicial process for 498A cases through fast-track courts to reduce the time and cost burden on the accused, making it less appealing for complainants to drag out cases for financial leverage.

Public Awareness Campaigns: Launch campaigns to educate the public about the proper use of Section 498A, emphasizing the consequences of misuse, fostering a culture of social accountability.